Пантеизм

Pantheism is the belief that the universe (or nature as the totality of everything) is identical with divinity,<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> or that everything composes an all-encompassing, immanent God.<ref name="Edwards">Шаблон:Cite book</ref> Pantheists thus do not believe in a distinct personal or anthropomorphic god.<ref>A Companion to Philosophy of Religion edited by Charles Taliaferro, Paul Draper, Philip L. Quinn, p.340 "They deny that God is "totally other" than the world or ontologically distinct from it."</ref> Some Eastern religions are considered to be pantheistically inclined.

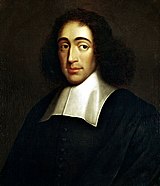

Pantheism was popularized in the West as both a theology and philosophy based on the work of the 17th-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza,<ref name=Picton/>Шаблон:Rp whose Ethics was an answer to Descartes' famous dualist theory that the body and spirit are separate.<ref name=Plumptre /> Spinoza held the monist view that the two are the same, and monism is a fundamental part of his philosophy. He was described as a "God-intoxicated man," and used the word God to describe the unity of all substance.<ref name=Plumptre>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> Although the term pantheism was not coined until after his death, Spinoza is regarded as its most celebrated advocate.<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref>

Definitions

Pantheism is derived from the Greek roots pan (meaning "all") and theos (meaning "God"). There are a variety of definitions of pantheism. Some consider it a theological and philosophical position concerning God.<ref name=Picton>Шаблон:Cite book</ref>Шаблон:Rp

As a religious position, some describe pantheism as the polar opposite of atheism.<ref name=Plumptre>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> From this standpoint, pantheism is the view that everything is part of an all-encompassing, immanent God.<ref name="Edwards"/> All forms of reality may then be considered either modes of that Being, or identical with it.<ref name="Deity">Owen, H. P. Concepts of Deity. London: Macmillan, 1971, p. 65.</ref> Others hold that pantheism is a non-religious philosophical position. To them, pantheism is the view that the Universe and God are identical.;<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> in other words: that the Universe (with all its divine extensions, planets, suns, galaxies, thrones and creatures) is what people and religions call "God".

History

The first known use of the term pantheism was by the English mathematician Joseph Raphson in his work De spatio reali, written in Latin and published in 1697.<ref>Ann Thomson; Bodies of Thought: Science, Religion, and the Soul in the Early Enlightenment, 2008, page 54.</ref> In De spatio reali, Raphson begins with a distinction between atheistic ‘panhylists’ (from the Greek roots pan, "all", and hyle, "matter"), who believe everything is matter, and ‘pantheists’ who believe in “a certain universal substance, material as well as intelligent, that fashions all things that exist out of its own essence.”<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> <ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref> Raphson found the universe to be immeasurable in respect to a human's capacity of understanding, and believed that humans would never be able to comprehend it.<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref>

The term was borrowed and first used in English by the Irish writer John Toland in his work of 1705 Socinianism Truly Stated, by a pantheist. John Toland was influenced by both Spinoza and Bruno, and used the terms 'pantheist' and 'Spinozist' interchangeably.<ref>R.E. Sullivan, "John Toland and the Deist controversy: A Study in Adaptations", Harvard University Press, 1982, p. 193</ref> In 1720 he wrote the Pantheisticon: or The Form of Celebrating the Socratic-Society in Latin, envisioning a pantheist society which believed, "all things in the world are one, and one is all in all things ... what is all in all things is God, eternal and immense, neither born nor ever to perish."<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref><ref>Toland, John, Pantheisticon, 1720; reprint of the 1751 edition, New York and London: Garland, 1976, p 54</ref> He clarified his idea of pantheism in a letter to Gottfried Leibniz in 1710 when he referred to "the pantheistic opinion of those who believe in no other eternal being but the universe".<ref>Honderich, Ted, The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford University Press, 1995, p.641: "First used by John Toland in 1705, the term 'pantheist' designates one who holds both that everything there is constitutes a unity and that this unity is divine."</ref><ref>Thompson, Ann, Bodies of Thought: Science, Religion, and the Soul in the Early Enlightenment, Oxford University Press, 2008, p 133, ISBN 9780199236190</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">Paul Harrison, Elements of Pantheism, 1999.</ref>

Although the term "pantheism" did not exist before the 17th century, various pre-Christian religions and philosophies can be regarded as pantheistic. Pantheism is similar to the ancient Hindu philosophy of Advaita (non-dualism) to the extent that the 19th-century German Sanskritist Theodore Goldstücker remarked that Spinoza's thought was "... a western system of philosophy which occupies a foremost rank amongst the philosophies of all nations and ages, and which is so exact a representation of the ideas of the Vedanta, that we might have suspected its founder to have borrowed the fundamental principles of his system from the Hindus."<ref>Literary Remains of the Late Professor Theodore Goldstucker, W. H. Allen, 1879. p32.</ref>

Others include some of the Presocratics, such as Heraclitus and Anaximander.<ref>Thilly, Frank, "Pantheism", in Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, Part 18, Hastings, James (Ed.), Kessinger Publishing, 2003 (reprint, originally published 1908), p 614, ISBN 9780766136953.</ref> The Stoics were pantheists, beginning with Zeno of Citium and culminating in the emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius. During the pre-Christian Roman Empire, Stoicism was one of the three dominant schools of philosophy, along with Epicureanism and Neoplatonism.<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref><ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> The early Taoism of Lao Zi and Zhuangzi is also sometimes considered pantheistic.<ref name="ReferenceA"/>

The Catholic church regarded pantheism as heresy.<ref>Collinge, William, Historical Dictionary of Catholicism, Scarecrow Press, 2012, p 188, ISBN 9780810879799.</ref> Giordano Bruno, an Italian monk who was burned at the stake in 1600 for heresy, is considered by some to be a pantheist.<ref>McIntyre, James Lewis, Giordano Bruno, Macmillan, 1903, p 316.</ref> Baruch Spinoza's Ethics, finished in 1675, was the major source from which pantheism spread.<ref>Genevieve Lloyd, Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Spinoza and The Ethics (Routledge Philosophy Guidebooks), Routledge; 1 edition (2 October 1996), ISBN 978-0-415-10782-2, Page: 24</ref>

In 1785, a major controversy about Spinoza's philosophy between Friedrich Jacobi, a critic, and Moses Mendelssohn, a defender, known in German as the Pantheismus-Streit, helped to spread pantheism to many German thinkers in the late 18th and 19th centuries.<ref>Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (plato.stanford.edu).</ref>

For a time during the 19th century pantheism was the theological viewpoint of many leading writers and philosophers, attracting figures such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge in Britain; Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel in Germany; and Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau in the United States. Seen as a growing threat by the Vatican, it came under attack 1862 in the Syllabus of Errors of Pius IX.<ref>Syllabus of Errors 1.1 (papalencyclicals.net).</ref>

In the mid-eighteenth century, the English theologian Daniel Waterland defined pantheism as: "It supposes God and nature, or God and the whole universe, to be one and the same substance—one universal being; insomuch that men's souls are only modifications of the divine substance."<ref name=Worman>Worman, J. H., "Pantheism", in Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, Volume 1, John McClintock, James Strong (Eds), Harper & Brothers, 1896, pp 616–624.</ref><ref>Worman cites Waterland, Works, viii, p 81.</ref> In the early nineteenth century, the German theologian Julius Wegscheider defined pantheism as the belief that God and the world established by God are one and the same.<ref name=Worman/><ref>Worman cites Wegscheider, Inst 57, p 250.</ref>

In the late 20th century, pantheism was often declared to be the underlying theology of Neopaganism,<ref>Margot Adler, Drawing Down the Moon, Beacon Press, 1986.</ref> and Pantheists began forming organizations devoted specifically to Pantheism and treating it as a separate religion.<ref name="ReferenceA"/>

Recent developments

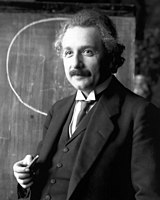

In 2008, one of Albert Einstein's letters, written in 1954 in German, in which he dismissed belief in a personal God, was sold at auction for more than US$330,000. Einstein wrote, "We followers of Spinoza see our God in the wonderful order and lawfulness of all that exists and in its soul ["Beseeltheit"] as it reveals itself in man and animal," in a letter to Eduard Büsching (25 October 1929) after Büsching sent Einstein a copy of his book Es gibt keinen Gott. Einstein responded that the book only dealt with the concept of a personal God and not the impersonal God of pantheism. "I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly," he wrote in another letter in 1954.<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref>

Pantheism is mentioned in a Papal encyclical in 2009<ref name=Caritas>Caritas In Veritate, 7 July 2009.</ref> and a statement on New Year's Day in 2010,<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref> criticizing pantheism for denying the superiority of humans over nature and "seeing the source of manШаблон:'s salvation in nature".<ref name=Caritas/> In a review of the 2009 film Avatar, Ross Douthat, an author, described pantheism as "Hollywood’s religion of choice for a generation now".<ref>Heaven and Nature, Ross Douthat, New York Times, 20 December 2009</ref>

In 2011, a letter written in 1886 by William Herndon, Abraham Lincoln's law partner, was sold at auction for US$30,000.<ref name=Letter>Шаблон:Cite web</ref> In it, Herndon writes of the U.S. President's evolving religious views, which included pantheism. Шаблон:Quote

The subject is understandably controversial, but the contents of the letter is consistent with Lincoln's fairly lukewarm approach to organized religion.<ref name=Lincoln />

Categorizations

There are multiple varieties of pantheism<ref name="Stanford">Шаблон:Cite web</ref>Шаблон:Rp which have been placed along various spectra or in discrete categories.

Degree of determinism

The American philosopher Charles Hartshorne used the term Classical Pantheism to describe the deterministic philosophies of Baruch Spinoza, the Stoics, and other like-minded figures.<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> Pantheism (All-is-God) is often associated with monism (All-is-One) and some have suggested that it logically implies determinism (All-is-Now).<ref name="Goldsmith">Шаблон:Cite book</ref><ref>F.C. Copleston, "Pantheism in Spinoza and the German Idealists," Philosophy 21, 1946, p. 48</ref><ref>Literary and Philosophical Society of Liverpool, "Proceedings of the Liverpool Literary & Philosophical Society, Volumes 43–44", 1889, p 285</ref><ref>John Ferguson, "The Religions of the Roman Empire", Cornell University Press, 1970, p 193</ref> Albert Einstein explained theological determinism by stating,<ref>Шаблон:Cite book p. 391 "I am a determinist"</ref> "the past, present, and future are an 'illusion'". This form of pantheism has been referred to as "extreme monism", in whichШаблон:Spaced ndash in the words of one commentatorШаблон:Spaced ndash "God decides or determines everything, including our supposed decisions."<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> Other examples of determinism-inclined pantheisms include those of Ralph Waldo Emerson,<ref>Dependence and Freedom: The Moral Thought of Horace Bushnell By David Wayne Haddorff [1] Emerson's belief was "monistic determinism".

- Creatures of Prometheus: Gender and the Politics of Technology By Timothy Vance Kaufman-Osborn, Prometheus ((Writer)) [2] "Things are in a saddle, and ride mankind."

- Emerson's position is "soft determinism" (a variant of determinism) [3]

- "The 'fate' Emerson identifies is an underlying determinism." (Fate is one of Emerson's essays) [4]</ref> and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.<ref>"Hegel was a determinist" (also called a combatibilist a.k.a. soft determinist) [5]

- "Hegel and Marx are usually cited as the greatest proponents of historical determinism" [6]</ref>

However, some have argued against treating every meaning of "unity" as an aspect of pantheism,<ref>Шаблон:Cite journal</ref> and there exist versions of pantheism that regard determinism as an inaccurate or incomplete view of nature. Examples include the beliefs of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling and William James.<ref>

- Theories of the will in the history of philosophy By Archibald Alexander p 307 Schelling holds "that the will is not determined but self-determined." [7]

- The Dynamic Individualism of William James by James O. Pawelski p 17 "[His] fight against determinism" "My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will." [8]

</ref>

Degree of belief

It may also be possible to distinguish two types of pantheism, one being more religious and the other being more philosophical. The Columbia Encyclopedia writes of the distinction:

- "If the pantheist starts with the belief that the one great reality, eternal and infinite, is God, he sees everything finite and temporal as but some part of God. There is nothing separate or distinct from God, for God is the universe. If, on the other hand, the conception taken as the foundation of the system is that the great inclusive unity is the world itself, or the universe, God is swallowed up in that unity, which may be designated nature."<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref>

Religious inclined pantheisms include some forms of Hinduism while philosophical inclined pantheisms include Stoicism.

Other

In 1896, J. H. Worman, a theologian, identified seven categories of pantheism: Mechanical or materialistic (God the mechanical unity of existence); Ontological (fundamental unity, Spinoza); Dynamic; Psychical (God is the soul of the world); Ethical (God is the universal moral order, Johann Gottlieb Fichte); Logical (Hegel); and Pure (absorption of God into nature, which Worman equates with atheism).<ref name=Worman/>

More recently, Paul D. Feinberg, professor of biblical and systematic theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, also identified seven categories of pantheism: Hylozoistic; Immanentistic; Absolutistic monistic; Relativistic monistic; Acosmic; Identity of opposites; and Neoplatonic or emanationistic.<ref>Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, edited by Walter A. Elwell, p. 887</ref>

Pantheism in religion

Philosopher Michael Levine has said that there may be more pantheists than theists worldwide.<ref name="Levine" />Шаблон:Rp There are elements of pantheism in some forms of Christianity,<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref><ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref><ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref> Islam (Sufism), Buddhism, Judaism, Gnosticism, Neopaganism, and Theosophy as well as in several tendencies in many theistic religions. The Islamic religious tradition, in particular Sufism and Alevism, has a strong belief in the unitary nature of the universe and the concept that everything in it is an aspect of God itself, although their perspective, like many traditional perspectives, may lean closer to panentheism. Many other traditional and folk religions including African traditional religions<ref>Шаблон:Cite journal</ref> and Native American religions<ref name="Levine" />Шаблон:Rp<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref> can be seen as pantheistic, or a mixture of pantheism and other doctrines such as polytheism and animism. A variety of modern paganists also hold pantheistic views.<ref>Carpenter, Dennis D. (1996). "Emergent Nature Spirituality: An Examination of the Major Spiritual Contours of the Contemporary Pagan Worldview". In Lewis, James R.. Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2890-0. p 50</ref>

Hinduism

It is generally regarded that Hindu religious texts are the oldest known literature containing pantheistic ideas.<ref name="Plumptre" /> The Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism teaches that the Atman (true self; human soul) is indistinct from Brahman (the unknown reality of everything).<ref>Vivekananda, 1987</ref>

The branches of Hinduism teaching forms of pantheism are known as non-dualist schools.<ref>Bhaskarananda, Swami (1994), The Essentials of Hinduism: a comprehensive overview of the world's oldest religion, Seattle, WA: Viveka Press, ISBN 1-884852-02-5</ref> All Mahāvākyas (Great Sayings) of the Upanishads, in one way or another, seem to indicate the unity of the world with the Brahman.<ref>"A Survey of Hinduism: First Edition", by Klaus K. Klostermaier, p. 201</ref> It further says, "This whole universe is Brahman, from Brahman to a clod of earth."<ref>"Hindu Literature: Or the Ancient Books of India", P.115, by Elizabeth A. Reed</ref>

Taoism

In the tradition of its leading thinkers Lao Tzu and Zhuangzi, Taoism is comparable with pantheism, as the Tao is always spoken of with profound religious reverence and respect, similar to the way that pantheism discusses the "God" that is everything. The Tao te Ching never speaks of a transcendent God, but of a mysterious and numinous ground of being underlying all things. Zhuangzi emphasized the pantheistic content of Taoism even more clearly: "Heaven and I were created together, and all things and I are one." When Tung Kuo Tzu asked Zhuangzi where the Tao was, he replied that it was in the ant, the grass, the clay tile, even in excrement: "There is nowhere where it is not… There is not a single thing without Tao."<ref>Chuang Tzu – The butterfly philosopher (pantheism.net).</ref>

Organizations

Two organizations that specify the word pantheism in their title formed in the last quarter of the 20th century. The Universal Pantheist Society, open to all varieties of pantheists and supportive of environmental causes, was founded in 1975.<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref> The World Pantheist Movement is headed by Paul Harrison, an environmentalist, writer and a former vice president of the Universal Pantheist Society, from which he resigned in 1996. The World Pantheist Movement was incorporated in 1999 to focus exclusively on promoting a naturalistic version of pantheism,<ref>Шаблон:Cite web</ref> considered by some a form of religious naturalism.<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> It has been described as an example of "dark green religion" with a focus on environmental ethics.<ref name="Dark Green">Bron Raymond Taylor, "Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future", University of California Press 2010, pp 159–160.</ref>

Related concepts

Nature worship or nature mysticism is often conflated and confused with pantheism. It is pointed out by at least one expert in pantheist philosophy that Spinoza’s identification of God with nature is very different from a recent idea of a self identifying pantheist with environmental ethical concerns, Harold Wood, founder of the Universal Pantheist Society. His use of the word nature to describe his worldview is suggested to be vastly different than the "nature" of modern sciences. He and other nature mystics who also identify as pantheists use "nature" to refer to the limited natural environment (as opposed to man-made built environment). This use of "nature" is different than the broader use from Spinoza and other pantheists describing natural laws and the overall phenomena of the physical world. Nature mysticism may be compatible with pantheism but it may also be compatible with theism and other views.<ref>Levine, Michael, Pantheism: A Non-Theistic Concept of Deity, Psychology Press, 1994, ISBN 9780415070645, pgs 44, 274-275.

- "The idea that Unity that is rooted in nature is what types of nature mysticism (e.g. Wordsworth and Robinson Jeffers, Gary Snyder) have in common with more philosophically robust versions of pantheism. It is why nature mysticism and philosophical pantheism are often conflated and confused for one another."

- "[Wood's] pantheism is distant from Spinoza’s identification of God with nature, and much closer to nature mysticism. In fact it is nature mysticism

- "Nature mysticism, however, is as compatible with theism as it is with pantheism."

- "Surely what Wood understands by “nature,” its value etc., is vastly different from “nature” as seen by the natural sciences."

</ref>

Panentheism (from Greek πᾶν (pân) "all"; ἐν (en) "in"; and θεός (theós) "God"; "all-in-God") was formally coined in Germany in the 19th century in an attempt to offer a philosophical synthesis between traditional theism and pantheism, stating that God is substantially omnipresent in the physical universe but also exists "apart from" or "beyond" it as its Creator and Sustainer.<ref name="Cooper">John W. Cooper, The Other God of the Philosophers, Baker Academic, 2006</ref>Шаблон:Rp Thus panentheism separates itself from pantheism, positing the extra claim that God exists above and beyond the world as we know it.<ref name="Levine">Шаблон:Cite book</ref>Шаблон:Rp The line between pantheism and panentheism can be blurred depending on varying definitions of God, so there have been disagreements when assigning particular notable figures to pantheism or panentheism.<ref name="Cooper" />Шаблон:Rp<ref>Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Genealogy to Iqbal edited by Edward Craig, pg 100 [9].</ref>

Pandeism is another word derived from pantheism and is characterized as a combination of reconcilable elements of pantheism and deism.<ref>Шаблон:Cite book</ref> It assumes a Creator-deity which is at some point distinct from the universe and then merges with it, resulting in a universe similar to the pantheistic one in present essence, but differing in origin.

Panpsychism is the philosophical view held by many pantheists that consciousness, mind, or soul is a universal feature of all things.<ref>Seager, William and Allen-Hermanson, Sean, "Panpsychism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/panpsychism/ </ref> Some pantheists also subscribe to the distinct philosophical views hylozoism (or panvitalism), the view that everything is alive, and its close neighbor animism, the view that everything has a soul or spirit.<ref>Haught, John F. (1990). What Is Religion?: An Introduction. Paulist Press. p. 19.</ref>

See also

Footnotes

Further reading

- Amryc, C. Pantheism: The Light and Hope of Modern Reason, 1898. online

- Harrison, Paul, Elements of Pantheism, Element Press, 1999. preview

- Hunt, John, Pantheism and Christianity, William Isbister Limited, 1884. online

- Levine, Michael, Pantheism: A Non-Theistic Concept of Deity, Psychology Press, 1994, ISBN 9780415070645

- Picton, James Allanson, Pantheism: Its story and significance, Archibald Constable & Co., 1905. online.

- Plumptre, Constance E., General Sketch of the History of Pantheism, Cambridge University Press, 2011 (reprint, originally published 1879), ISBN 9781108028028 online

- Russell, Sharman Apt, Standing in the Light: My Life as a Pantheist, Basic Books, 2008, ISBN 0465005179

- Urquhart, W. S. Pantheism and the Value of Life, 1919. online

External links

Шаблон:Wikiquote Шаблон:Wiktionary

- Шаблон:Sep entry

- Pantheism entry by Michael Levine (earlier article on pantheism in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- Шаблон:Dmoz

- The Pantheist Index, pantheist-index.net

- An Introduction to Pantheism (wku.edu)

- Шаблон:CathEncy

- The Universal Pantheist Society (pantheist.net)

- The World Pantheist Movement (pantheism.net)

- Pantheism and Judaism (chabad.org)